A Guide To Tamahagane – Japan’s Rarest Steel

Jump to:

Japan has a long and rich history of making swords, knives, and other blades. You may be familiar with old Japanese movies depicting samurai warriors wielding heavy steel swords or katana. These swords are made with a rare type of steel called Tamahagane, which dates back to the 6th Century AD in Japan.

In this post, we shall examine the history of steel manufacturing and Tamahagane in particular, look at where it is produced, consider what it is used for, and look at the entire process of forging blades from ironsand. We shall start, however, by looking at what Tamahagane is.

What Is Tamahagane?

The Kanji characters used in Tamahagane are “玉” meaning “ball” and “鋼” meaning steel. Although there has been some suggestion that it was named such because the steel was originally used to make cannon balls in the Meiji era, most people consider the term to mean “jeweled steel” or “precious steel”. The method used to make Tamahagane is an ancient technique called Tatara Seitetsu (which roughly translates as Tatara ironmaking), in which iron of high purity is produced by reducing ironsand at relatively low temperatures using charcoal in a clay furnace. This technique has been practiced in Japan since around the sixth century.

So, what is so special about the process of producing Tamahagane steel through Tatara ironmaking? When making steel, iron is heated to a point where it becomes completely liquid. However, once it becomes fully liquid, it is not possible to remove impurities. With Tatara-iron making, ironsand is burned to 1400℃ where it is in a semi-solid state, but the impurities become liquid, so they can be removed, allowing for the production of high-purity steel. Before we go on to look at Tamahagane in detail, let us take a brief look at its history.

The History of Tamahagane

The development of Tamahagane, and specifically the Tatara ironmaking method, has been heavily influenced by geographical factors. As most of Japan’s coastal deposits of iron ore would involve expensive deep-sea mining, the use of iron ore as a resource for steelmaking is not cost-effective. However, Japan is (in some senses of the word) “blessed” with an abundance of volcanoes, and areas with ancient volcanic rocks and basalt are a plentiful source of ironsand, which is the primary raw material for Tamahagane. From the 6th Century AD, iron began to be produced using this ironsand, and the tradition has continued for more than 1400 years. There have, however, been several historical hiccups along the way.

Today, Japanese swords and their production techniques are protected as an important intangible cultural property and passed down from generation to generation. However, there was a time after World War II when the industry was in crisis. The technique of Tamahagane, which is indispensable for making Japanese swords, had been studied for more than 1,000 years since the Kofun period and perfected in the Edo period as “modern Tatara”. However, the industry shrunk rapidly due to a sword ban that was enforced in Japan in 1876, and in the Taisho period (1912-1926), it was pushed aside in favor of more cost-effective steel that could be mass-produced as part of the move towards modern industrialization. It was briefly revived to make military swords during the war, but the American occupying forces banned swords again in 1945. At this point, it was in danger of becoming a lost art.

However, a white knight appeared in the form of a team formed in 1977, consisting of the Japanese Swordsmith Association and Hitachi Metal Company, which revived the technology, and the Tamahagane production process was later recognized by the Minister of Education as a traditional craft designated for preservation.

Where is Tamahagane Produced

The raw material, ironsand (Satetsu), which is used to make Tamahagane steel is found in the Okuizumo area of Shimane Prefecture, which is in the Chugoku region of the main Japanese island of Honshu and consists of two types, Masa and Sasetsu, with Masa being of the higher quality. The two types differ according to the percentage of iron ore and carbon that can be converted into steel. This region is also home to the only historical furnace, called a Tatara, for making Tamahagane. Although the ironsand is used by craftsmen in other parts of the country for making Tamahagane, it is a technique only known by a select few. It is said, for example, that there are only two people who can make Tamahagane on their own in Tokyo.

What Is Tamahagane Used For?

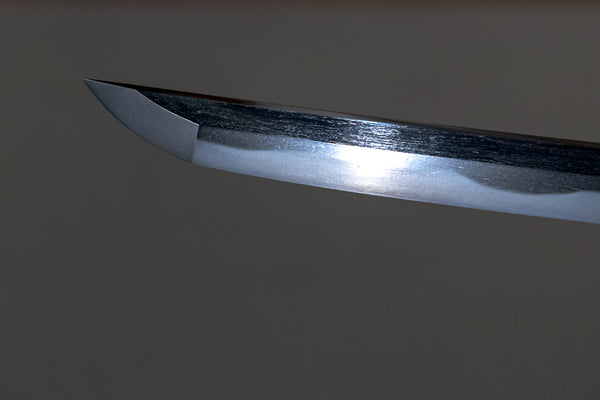

The requirements for a sword or, in fact, any blade, are that it “does not break and does not bend, but still cuts well.” Tamahagane ticks all the boxes in this regard, being strong, flexible, rust-resistant, and sharp. These qualities are partly achieved through the purity of the steel, which has a carbon content of approximately 0.3 to 1.5%.

Another aspect that makes Tamahagane ideal for this purpose is its non-metallic inclusion elements (the oxides, sulfides, and other non-metallic substances contained in metals) in Tamahagane, which are extremely soft and stretchable, thus allowing the blade to give but not break on impact, making it an ideal iron material for swords.

Japanese swords can become more robust through repeated forging, and these elements create beautiful patterns in the base iron making the swords “one of a kind”, and also improving the sharpness of the sword.

Although, in rare cases, kitchen knives may be made with Tamahagane, due to its limited production, and the fact that only swords that are created with Tamahagane can be referred to as “katana” in Japan, priority is given to creating swords (for ornamental purposes) and keeping the traditional craft of sword making alive.

From Ironsand To Blade

The mystique around Tamahagane and its value is further increased by the fact that the traditional craft of Tatara ironmaking cannot be reproduced by a machine and involves painstaking manual labor. We shall discuss the various aspects of the process in detail below.

Ironsand Collection

River sand or dust is collected from riverbeds, beaches, and hills where it has accumulated, and is then filtered until only the purest ironsand is left. Previously, this was performed with sluice boxes, which filter the relatively heavy iron elements through water filtration. Nowadays, a magnet will be used to extract the iron grains. These are then placed into a rectangular clay furnace called a Tatara.

Smelting

The next process involves smelting the ironsand. In addition to the ironsand, charcoal is added, which provides hardness and strength to the steel produced. They are combined and heated to a temperature of about 1400℃ in the Tatara. Ironsand is manually added to the Tatara every ten minutes or so, with alternate layers of charcoal, for about three days. This labor-intensive approach means that mass production of Tamahagane is difficult, and also accounts for its relatively high price.

Collection

When all of the iron has been converted into Tamahagane, the collection process begins. As much of the steel accumulates on the sides or bottom of the Tatara, the Tatara will be demolished to aid in the collection process. For this reason, a Tatara tub is never reused. Once it has all been collected, it is shipped to the various locations where it will be forged into various tools (nearly always swords). Two types of Tamahagane are produced by this process: high and low-carbon steel. As will be discussed later, both are important.

Removing of Impurities

From this point, the process moves to the swordsmith who carries out the tasks of hammering, heating, and folding the steel. The swordsmith heats the various Tamahagane chunks of steel in a separate furnace and then hammers them into a collection of flat wafers. These wafers are then combined and inserted in a high-temperature forge. The slag is removed, and the swordsmith judges the right amount of carbon concentration while hammering the bars.

Forging Swords

The high-carbon steel is formed into a U-shaped channel after these impurities are removed, but the sword cannot rely simply on this high-carbon steel as the sword will be brittle if it is too hard. For this reason, lower carbon steel is heated and sandwiched between the layers of hard steel. When the blade is softer on the inside and harder on the outside, it will become a sharp weapon while also having good tensile strength and durability. It is then formed into a sword-like shape.

Coating

After being shaped, the sword is coated with a special clay made from a mixture of clay charcoal. Both sides are coated with only a light coat on the blade’s sharp front edge. The blade is then heated again to around 1500℃.

Quenching

The final step involving the swordsmith is the quenching, or hardening process. The swordsmith submerges the blade in water, causing rapid cooling of the steel. The blade's cutting edge, which has the thinner layer of paste, hardens immediately. As the carbons are packed more tightly, the edge becomes harder and extremely sharp. The back portion of the sword has a thicker paste so it hardens more slowly and thus becomes more durable. Finally, the sword is polished and sharpened and fit with a handle, etc.

Tamahagane – The Jeweled Steel

As discussed, Tamahagane has pride of place among the steel manufactured in Japan (for a more general overview of Japanese steel, please see this article, and although once in danger of becoming a lost art, is now protected as a designated cultural property necessary for keeping the traditional craft of Japanese sword-making alive.

The production of Tamahagane involves several days of manual labor, and, in this sense, embodies the Japanese spirit of creating something truly valuable through effort.

2 comments

Hi Frank

Thank you for your comment.

Unfortunately, we do not sell iron sand.

However, large Japanese home centers or variety stores such as CAINZ or Tokyu Hands, which carry a wide range of DIY and hobby items, may have iron sand available for experiments and similar purposes.

Daitool,

I’m looking to purchase Japanese iron sand.

Frank Guilliani ,